- Two Thanksgiving Thoughts for the ACAPosted 11 years ago

- Shop til you Drop at the Healthcare Marketplace Part 2: Frustration!Posted 11 years ago

- An Early Casualty in the Affordable Care FightPosted 11 years ago

- Some Good News for a ChangePosted 11 years ago

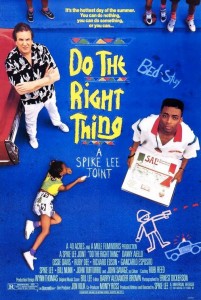

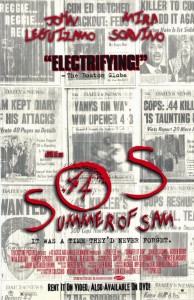

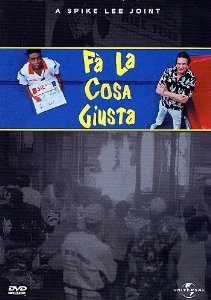

Three from Spike Lee: “Do the Right Thing” (1989), “Jungle Fever” (1991), “Summer of Sam” (1999)

Dan Walker On Film

Since I associate these three movies with each other, I thought it would be interesting to review them all in one shot, which was challenging. Two things I’m constantly told is to make my pieces shorter and minimize the asides. When I ask for recommendations on what to cut out, the suggestion is retracted. I’m open to constructive criticism and, in fact, constantly solicit it, the key word being “constructive.” If I didn’t think what I wrote added value, I wouldn’t write it. I really want to give the reader my take on a movie and I can usually accomplish that in much shorter reviews. The one for “Sullivan’s Travels”, even without the asides and anecdotes, was long because I wanted to emphasize how many interesting elements it had and their diversity. This one is different because I watch all three movies at least once a year so I’ve had years to digest and think about them. Even then, I had no idea this one would be so extensive when I started but I can’t find segments I’d cut from it and it’s still not all-inclusive. I repeat things intentionally for emphasis so I acknowledge any redundancies and I ignore timelines in making my points. I make a lot of parenthetical asides. I think parenthetically so that’s how I write, although I still try to curb my use of asides under normal circumstances. I’m not listing the casts of the movies under their titles like I usually do because I think identifying the actors and their characters in the piece is sufficient and the lists for all three movies would have been overload, which this review is already. I guess they would have been over-overload. I promise to go out of my way to make my next review succinct (don’t hold me to that). Because of its length, don’t think of this writing as a review; think of it as a book chapter or, better yet, a thesis (not that I ever wrote a thesis). I hope you find it enjoyable enough to revisit after you read it the first time because I think it’s dense enough that repeat readings will help you digest it better.

Since I associate these three movies with each other, I thought it would be interesting to review them all in one shot, which was challenging. Two things I’m constantly told is to make my pieces shorter and minimize the asides. When I ask for recommendations on what to cut out, the suggestion is retracted. I’m open to constructive criticism and, in fact, constantly solicit it, the key word being “constructive.” If I didn’t think what I wrote added value, I wouldn’t write it. I really want to give the reader my take on a movie and I can usually accomplish that in much shorter reviews. The one for “Sullivan’s Travels”, even without the asides and anecdotes, was long because I wanted to emphasize how many interesting elements it had and their diversity. This one is different because I watch all three movies at least once a year so I’ve had years to digest and think about them. Even then, I had no idea this one would be so extensive when I started but I can’t find segments I’d cut from it and it’s still not all-inclusive. I repeat things intentionally for emphasis so I acknowledge any redundancies and I ignore timelines in making my points. I make a lot of parenthetical asides. I think parenthetically so that’s how I write, although I still try to curb my use of asides under normal circumstances. I’m not listing the casts of the movies under their titles like I usually do because I think identifying the actors and their characters in the piece is sufficient and the lists for all three movies would have been overload, which this review is already. I guess they would have been over-overload. I promise to go out of my way to make my next review succinct (don’t hold me to that). Because of its length, don’t think of this writing as a review; think of it as a book chapter or, better yet, a thesis (not that I ever wrote a thesis). I hope you find it enjoyable enough to revisit after you read it the first time because I think it’s dense enough that repeat readings will help you digest it better.

Having said all that, here we go:

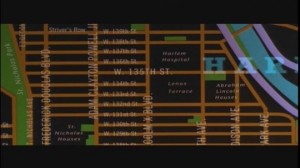

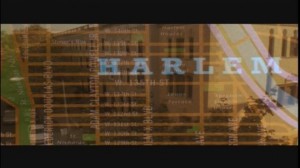

As I do every summer, I recently watched Spike Lee’s 1989 “Do the Right Thing”, 1991 “Jungle Fever” and 1999 “Summer of Sam.” Their New York City settings are a huge part of their appeal for me and the city is nothing but movie backdrops and supporting characters. I went to elementary school in Great Falls, Montana and junior high in Cheyenne, Wyoming and was envious of any kid that grew up in NYC because they were exposed to so much – in terms of volume, diversity, quality, and intensity – at an early age. As it turns out, I’m glad to have grown up where I did, having taken advantage of the wide-open spaces and natural beauty by being part of an avid hunting, fishing and nature-loving family. After living in the Bay Area, Los Angeles, Manhattan and the Midwest (two years of my life I’ll never get back), I appreciate the grounded, uncomplicated mentality I grew up around in the Rocky Mountain states. In living in Manhattan for eight years – and living out a childhood daydream – I loved it (especially every moment between the beginning of October and the end of the holidays), hated it (especially during the summer) and left it. I have pictures if you want to see ‘em.

As I do every summer, I recently watched Spike Lee’s 1989 “Do the Right Thing”, 1991 “Jungle Fever” and 1999 “Summer of Sam.” Their New York City settings are a huge part of their appeal for me and the city is nothing but movie backdrops and supporting characters. I went to elementary school in Great Falls, Montana and junior high in Cheyenne, Wyoming and was envious of any kid that grew up in NYC because they were exposed to so much – in terms of volume, diversity, quality, and intensity – at an early age. As it turns out, I’m glad to have grown up where I did, having taken advantage of the wide-open spaces and natural beauty by being part of an avid hunting, fishing and nature-loving family. After living in the Bay Area, Los Angeles, Manhattan and the Midwest (two years of my life I’ll never get back), I appreciate the grounded, uncomplicated mentality I grew up around in the Rocky Mountain states. In living in Manhattan for eight years – and living out a childhood daydream – I loved it (especially every moment between the beginning of October and the end of the holidays), hated it (especially during the summer) and left it. I have pictures if you want to see ‘em.

Along with directing all three movies, Lee wrote the first two himself and co-wrote the third with Victor Colicchio and Michael Imperioli (memorable as Spider in “Goodfellas” and Christopher Moltisanti on The Sopranos. Christopher’s death was one of the most powerful moments I’ve ever seen on a television show). When you think of early Lee, you generally think of his films as being black-themed but the first two are as much about Italian-Americans as they are about blacks, and “Summer of Sam” is more Italian-American than anything. Judging by these three movies, Lee has a love-hate relationship with Italian-Americans and shows them in both a positive light and a bad one.

Along with directing all three movies, Lee wrote the first two himself and co-wrote the third with Victor Colicchio and Michael Imperioli (memorable as Spider in “Goodfellas” and Christopher Moltisanti on The Sopranos. Christopher’s death was one of the most powerful moments I’ve ever seen on a television show). When you think of early Lee, you generally think of his films as being black-themed but the first two are as much about Italian-Americans as they are about blacks, and “Summer of Sam” is more Italian-American than anything. Judging by these three movies, Lee has a love-hate relationship with Italian-Americans and shows them in both a positive light and a bad one.

In Bedford-Stuyvesant (Brooklyn)-set “Do the Right Thing”, Sal (Oscar ®-nominated Danny Aiello) owns a pizzeria where he works with his two sons; angry, resentful, and racist Pino (John Turturro, in my favorite portrayal in the film), and easygoing Vito (Richard Edson, always interesting and the parking attendant who soared to the “Star Wars” theme in Cameron’s dad’s Ferrari in “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off”). Sal and his sons live in another Brooklyn neighborhood, likely Bensonhurst, one of the settings of “Jungle Fever.” The pizzeria’s other employee is delivery guy Mookie (Lee, in a very well written and well fleshed-out character).

Sal is paternal, understanding, patient and tough-love. All of those traits are tested repeatedly during the movie. Pino never hides his contempt for blacks and only drops his racist defense mechanisms, if only a little, when Mookie takes him aside to address Pino’s racism, especially since he takes the brunt of it. Mookie points out the fact that Pino’s favorite actor (Eddie Murphy), basketball player (Magic Johnson) and singer (Lee tells him it’s Prince but Pino insists it’s “Bruuuuuuuuuuuce”), in an insightful scene, are all black. In an extra dig at Pino’s hypocritical and self-contradicting racist attitude, Mookie says, “Look at your hair; it’s kinkier than mine. You know what they say about dark eye-talians.” Mookie doesn’t meet racism with racism; he tries to diffuse Pino’s impenetrable racism.

In “Jungle Fever”, the affair of married and black architect Flipper (Wesley Snipes long before his tax problems) with single and Italian-American Gina temp secretary assigned to him (Annabella Sciorra, who probably lost more than a few roles to Marisa Tomei and was Emmy-nominated for her portrayal of Tony Soprano’s unstable, volatile, and ultimately suicidal girlfriend, Gloria Trillo) is the basis for the storyline. It should be noted Flipper was upset when his discrimatory – in his eyes, preferential – request for a black temp was ignored. Flipper lives with his wife, Drew (Lonette McKee) and daughter in mostly-black Harlem in Manhattan and Gina lives with (and cooks for and cleans after) her father and brothers in mostly-Italian Bensonhurst in Brooklyn. This clip establishes the character of Gina and her relationship with her family (graphic language warning): Jungle Fever Gina dinner

A subplot that really doesn’t add much to the movie is that Flipper’s request/proposal to be made partner at his architectural firm is rejected by his bosses, played by Brad Dourif and Tim Robbins. It’s hard to tell if they’re racist themselves or if they implicitly let him know they find him belligerent and racist. There are no healthy interactions in the scenes they share, which is an ongoing point of the movie. The

A subplot that really doesn’t add much to the movie is that Flipper’s request/proposal to be made partner at his architectural firm is rejected by his bosses, played by Brad Dourif and Tim Robbins. It’s hard to tell if they’re racist themselves or if they implicitly let him know they find him belligerent and racist. There are no healthy interactions in the scenes they share, which is an ongoing point of the movie. The  shortcoming of the script is that Lee sacrifices a more interesting story and multi-dimensional characters for a story that strives to make a point in almost every scene and uses stereotypes to do it. The film’s insights and inspired performances, however, definitely compensate.

shortcoming of the script is that Lee sacrifices a more interesting story and multi-dimensional characters for a story that strives to make a point in almost every scene and uses stereotypes to do it. The film’s insights and inspired performances, however, definitely compensate.

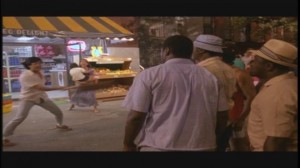

There’s a secondary and lesser mixed-race relationship between Paulie (Turturro reliably effective in a sad sack role as emphasized by his aimless walk and unflattering haircut), who runs a family shop that serves egg creams and sells newspapers, and Orin (Tyra Ferrell), a black patron. Orin really doesn’t have an interest in Paulie but acquiesces when he asks her out (left). While at the shop and to the point it seems to be part of his job description, Paul has to fend off the raceless or purposeless antagonism of a group of neighborhood guys (below) who spend their free time there, following the lead of Vinny (Nicholas Turturro, John’s brother).

Before her affair, Gina and Paulie were a couple. The reaction of the widowed (which adds to their bitterness) fathers of both Italian-American participants of the mixed-race relationships is the same but to different degrees. Gina’s father Mike (the charismatic and excessively macho Frank Vincent), in finding out about his daughter’s affair, is much more concerned that the guy is black than he is that he’s married, which is saying something for a Catholic. Catholics tend to be their most Catholic when it’s convenient for them and their interpretations of the religion are self-serving and of-the-moment.

In what had to be a very tough scene to film because it’s sure hard to watch, as Gina returns home from breaking up with Paulie, which was very hard on both, Mike pounces and explodes on her and beats her without inhibition. He is barely able to be restrained by his two sons (one played by Imperioli). He doesn’t smash a table lamp on Gina; he uses her body to smash a table lamp. He backhands, punches, pushes, throws and shakes her violently. He yells nonstop – I counted seven uses of the n-word – as he beats and bounces her off every available surface, saying he’d rather “have it be a mass murderer or child molester” than an n-word.

During the nonstop beating/yelling he says, “Your mother’s turning over in her grave! I raised you to be a good Catholic girl! You’re a disgrace!”, and the clincher, “I wish your mother had lived and you had died!” When Gina’s friends (Debbie Mazar and the late Gina Mastrogiacomo, who also play friends and Henry Hill’s girlfriends in “Goodfellas”) come to help her move out immediately following the beating (right) – which draws out the entire neighborhood – Mike continues yelling himself hoarse from an upper-level window, “I’d rather stab myself in the heart than be the father of a n––r lover!” That’s hate. In that scene, racism and religion-based hate are in a battle of their own over which is more the point. Here’s that very powerful and tough-to-watch scene (I’m intentionally not putting up a still): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jbk0S48YZMc The song Stevie Wonder is ironically singing during the scene is “These Three Words”, which is about expressing your love to your parents, children, siblings and friends.

When Paulie reluctantly yet defiantly tells his angry and seemingly homebound father Lou (the late two-time Oscar winner Anthony Quinn, who, like Rita Hayworth, is of Mexican descent) he’s going on a date with Orin, Lou says, “You don’t bring no brown sugar home to this house. If your mother was alive, she’d turn over in her grave”, which really is a good line, especially given Quinn’s authentically emphatic Italian delivery (left).

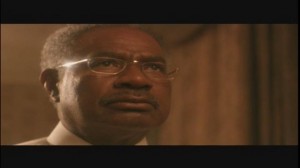

The reaction of Flipper’s parents, The Good Reverend Doctor and Lucille Purify (the late Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, a couple in real life before his passing) is different than that of Mike and Lou, although it’s still one of disapproval. Their objection is more about Flipper being married – although race is still an issue – and is not violent or blatantly hostile. Like Mike and Lou and as implied by his name, The Good Reverend Doctor (below) is very religious and, like Mike and Lou, he uses his religion to justify his hateful reaction to the couple. After inviting Gina to his home for dinner and without raising his voice and in flowery, biblical language, he is verbally abusive to her as she’s a captive audience at the table with Flipper and his parents (right).

The reaction of Flipper’s parents, The Good Reverend Doctor and Lucille Purify (the late Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, a couple in real life before his passing) is different than that of Mike and Lou, although it’s still one of disapproval. Their objection is more about Flipper being married – although race is still an issue – and is not violent or blatantly hostile. Like Mike and Lou and as implied by his name, The Good Reverend Doctor (below) is very religious and, like Mike and Lou, he uses his religion to justify his hateful reaction to the couple. After inviting Gina to his home for dinner and without raising his voice and in flowery, biblical language, he is verbally abusive to her as she’s a captive audience at the table with Flipper and his parents (right).

Religious people often use religion as leverage to be hateful and judgmental, an excellent and necessary point Lee should be acknowledged for making so well. In this movie, his characters use religion to justify brutal physical abuse and even murder, in both cases directed at the child of the abuser/murderer.

Gina gets it from every direction (her role is that of an emotional tennis ball), including her girlfriends (right), although they are ultimately supportive. The irony of their support and consistent with the the hypocritical characters pervasive in the film is it’s implied it was through Gina’s girlfriends that Mike found out in the first place. That Lee would portray stereotypical New Yorkers as nosy, judgmental, gossipy instigators should not be lost on anyone.

In “Summer of Sam”, the racism is minimal and limited to a dinner conversation where participants argue over who was better between Mantle and Mays, an argument that will go on into perpetuity. Arguing is the comfort zone of New Yorkers. New Yorkers don’t converse, they compete. There’s a scene where Ruby (Jennifer Esposito) gets called a “dago wop skank” by her just-dumped boyfriend because she won’t accompany him on a weekend Catskills trip (above). Gee, I wonder why; I thought that was how New Yorkers serenaded their women.

Esposito and Imperioli (right) were originally cast in the lead roles but scheduling conflicts limited both to lesser characters and the film suffers as a result. The lead, Vinnie, is instead portrayed by Colombian born and not at all Italian looking John Leguizamo, a guy I admit is a talented dervish. He was a good and well cast Toulouse-Lautrec in “Moulin Rouge!” and funny as the voice of Sid in the “Ice Age” movies. I read that he was so good and got so much into his role as a drag queen in “To Wong Foo Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar” that co-stars Snipes and Patrick Swayze were concerned for him.

Having said that, I think he lacks a leading-actor screen presence and voice the same way Madonna does (Meryl Streep should have been Evita and should have hand-written a four-page essay pleading her case for the role if that was the criterion for getting the part, which it was. Can you imagine how Madonna would have similarly brought down “Chicago” had she been cast as Roxie Hart, which was a much-discussed rumor at the time?). The movie would have been more authentic and the portrayal more believable had an appropriate Italian actor been cast in the role. I also couldn’t buy his portrayal as Benny Blanco, the up-and-coming mobster rival of Al Pacino’s character in De Palma’s 1993 “Carlito’s Way.”  Academy Award® winner Mira Sorvino plays Vinnie’s wife Dionna and is sufficient – especially in the scenes where she’s fearful of the killer and insecure about her marriage – but the movie would have been better with Esposito in that role (she used to be a dancer). When you watch Sorvino dance with Leguizamo, you feel like you’re eavesdropping on a dancing lesson (right).

Academy Award® winner Mira Sorvino plays Vinnie’s wife Dionna and is sufficient – especially in the scenes where she’s fearful of the killer and insecure about her marriage – but the movie would have been better with Esposito in that role (she used to be a dancer). When you watch Sorvino dance with Leguizamo, you feel like you’re eavesdropping on a dancing lesson (right).

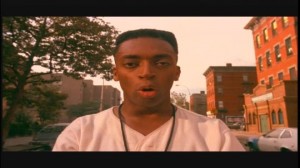

Several things are fascinating about the portrayal of blacks in these movies and they’re to Lee’s credit. In all three, the characters Lee himself portrays are less than ideal, ethical or competent. In “Do the Right Thing”, Lee’s Mookie is an unmarried and irresponsible father of one whose support of his son’s mother, Tina, played by Rosie Perez, is sporadic and unreliable. Rosie’s contribution to the movie, especially in the Public Enemy “Fight the Power” opening credit sequence (above), can best and most appropriately be described as ““caliente y picante” and she fires up every scene she’s in. During the scenes where she’s not angry, she projects warmth and charm, even when she’s being foul-mouthed.

Mookie also prevents pizza orders from being called in because he uses the pizzeria phone to sweet-talk to Tina (right) and, while delivering pizzas, stops at Tina’s for 90-minute stretches. Sal doesn’t have much of a problem with any of that as long as the pizzas get delivered, although he does give Mookie a short, stern warning at one point in the film. As supportive and fatherly as Sal treats Mookie – he even tells Mookie, “you’ve always been like a son to me” – Mookie doesn’t return the favor and keeps an emotional distance from Sal and is dismissive in his response to Sal’s warning.

Mookie also prevents pizza orders from being called in because he uses the pizzeria phone to sweet-talk to Tina (right) and, while delivering pizzas, stops at Tina’s for 90-minute stretches. Sal doesn’t have much of a problem with any of that as long as the pizzas get delivered, although he does give Mookie a short, stern warning at one point in the film. As supportive and fatherly as Sal treats Mookie – he even tells Mookie, “you’ve always been like a son to me” – Mookie doesn’t return the favor and keeps an emotional distance from Sal and is dismissive in his response to Sal’s warning.  Other than the scenes where Mookie tells Sal and his own cool, stable, and responsible sister Jade (Lee’s sister, Joei) he doesn’t want them talking to each other (left), Mookie doesn’t come across as overtly racist. He even tries to diffuse Buggin Out’s racist and antagonistic behavior towards Sal’s family and establishment as well as his attempt to start a boycott of Sal’s. He gets along well with Vito, but the line is definitely there and is crossed with his response to the police choke-hold-induced death of Radio Raheem (an intimidating presence the entire movie and whose portrayal is nailed by Bill Nunn, especially in the death scene).

Other than the scenes where Mookie tells Sal and his own cool, stable, and responsible sister Jade (Lee’s sister, Joei) he doesn’t want them talking to each other (left), Mookie doesn’t come across as overtly racist. He even tries to diffuse Buggin Out’s racist and antagonistic behavior towards Sal’s family and establishment as well as his attempt to start a boycott of Sal’s. He gets along well with Vito, but the line is definitely there and is crossed with his response to the police choke-hold-induced death of Radio Raheem (an intimidating presence the entire movie and whose portrayal is nailed by Bill Nunn, especially in the death scene).

That scene, where the blacks are hostile, belligerent, and threatening from beginning to its literal end:

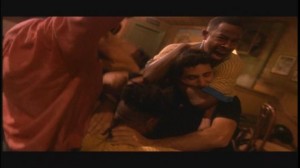

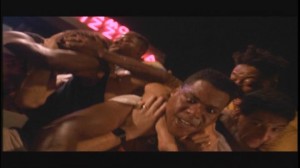

I originally wasn’t going to post any pictures of the scene but it’s so visual, I thought I’d include a few. Once I started, I couldn’t stop. Note the use of angled shots to emphasize something foreboding or threatening. Also, although you can’t see in the stills, Radio’s box flashes red lights as it’s in front of the camera on the counter. Flashing red lights always indicate trouble or urgency. The next two paragraphs offer a partial narration of the pictures. I want to do a review, not an in-depth analysis. I can’t upload it myself but here’s part of the scene on youtube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TQ4y7GPeFBY

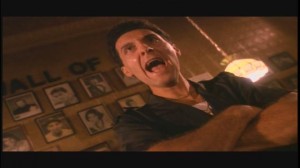

Sal lets the hostile teens into the pizzeria even though he’s closing up after a particularly lucrative and satisfying day of business. Even after he does them that favor, the group is belligerent and loud while they sit down and wait for their pizza. Their loudness is abruptly stopped and all heads turn in reaction to Radio and Buggin as they enter Sal’s with Radio’s boom box playing, at full volume, Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” (the film’s theme and the only song he plays in the movie and he has his boom box on all the time, hence his name). The stress level becomes amped up when Buggin – and Esposito uses every fiber of his being in this scene – rabidly screams and curses, demanding Sal put up black pictures on his wall. The pictures are only an excuse for Buggin to start the attack on Sal’s he plots and recruits for from the film’s onset. The teens recover from their shock and begin instigating the situation and further raising the intensity level of the scene. Finally pushed far past the point of tolerance and in the face of being violently threatened, Sal is driven to make references to Africa, jungle music and ultimately to use the n-word before he uses his baseball bat to smash the boom box, which Radio slams on the counter, daring Sal to turn off. The shop is silenced in shocked reaction for several seconds as everyone waits for the next move. Radio then grabs Sal by the collar, pulling him over the counter and onto the floor, pummeling him. The fight’s momentum takes itself outside, the neighborhood gathers around, the police arrive, make their way through the frenzied crowd and three of them pull Radio off Sal and Rick Aiello’s (Danny’s son) character applies the choke hold, killing Radio in front of the mob. After stuffing Radio and Buggin into their cars, the cops leave the scene for Sal and his sons to fend for themselves against the retaliatory and confrontational mob, who blame Sal’s family for the killing.

Sal lets the hostile teens into the pizzeria even though he’s closing up after a particularly lucrative and satisfying day of business. Even after he does them that favor, the group is belligerent and loud while they sit down and wait for their pizza. Their loudness is abruptly stopped and all heads turn in reaction to Radio and Buggin as they enter Sal’s with Radio’s boom box playing, at full volume, Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” (the film’s theme and the only song he plays in the movie and he has his boom box on all the time, hence his name). The stress level becomes amped up when Buggin – and Esposito uses every fiber of his being in this scene – rabidly screams and curses, demanding Sal put up black pictures on his wall. The pictures are only an excuse for Buggin to start the attack on Sal’s he plots and recruits for from the film’s onset. The teens recover from their shock and begin instigating the situation and further raising the intensity level of the scene. Finally pushed far past the point of tolerance and in the face of being violently threatened, Sal is driven to make references to Africa, jungle music and ultimately to use the n-word before he uses his baseball bat to smash the boom box, which Radio slams on the counter, daring Sal to turn off. The shop is silenced in shocked reaction for several seconds as everyone waits for the next move. Radio then grabs Sal by the collar, pulling him over the counter and onto the floor, pummeling him. The fight’s momentum takes itself outside, the neighborhood gathers around, the police arrive, make their way through the frenzied crowd and three of them pull Radio off Sal and Rick Aiello’s (Danny’s son) character applies the choke hold, killing Radio in front of the mob. After stuffing Radio and Buggin into their cars, the cops leave the scene for Sal and his sons to fend for themselves against the retaliatory and confrontational mob, who blame Sal’s family for the killing.

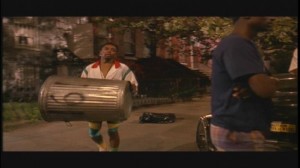

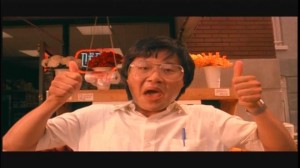

In the scene of the movie, Lee’s directing (and acting) career and possibly Ernest Dickerson’s DP career even after the explosive and deadly scene that preceded it – after looking at Sal during the crowd’s silent reaction to Radio’s death, Mookie crosses the street, empties a metal trash can, carries it back across the street and yells “HATE!” as he throws it through the window of Sal’s. The moment of impact is shown twice from different angles and, in an understatement, is jarring and memorable. The scene is as powerful as the impact with which the can hits the window and it ignites the riot that tears apart, loots, and burns down the pizzeria while Sal and his sons are helpless to do anything but watch. The frenzied mob, following the lead of ML (Paul Benjamin), who had previously expressed resentment at how enterprising Korean storekeepers are, turns its attention toward the Korean-owned grocery store, which is defended with a swinging broom by the owner, Sonny (Steve Park who, in a great bit of trivia, also played the non-sequitur and not-at-all-similar character Mike Yanagita in “Fargo” and is both times outstanding) until they decide there’s no need to damage his store, which is great for Sonny but it amplifies the alienation Sal and his sons feel.

In the scene of the movie, Lee’s directing (and acting) career and possibly Ernest Dickerson’s DP career even after the explosive and deadly scene that preceded it – after looking at Sal during the crowd’s silent reaction to Radio’s death, Mookie crosses the street, empties a metal trash can, carries it back across the street and yells “HATE!” as he throws it through the window of Sal’s. The moment of impact is shown twice from different angles and, in an understatement, is jarring and memorable. The scene is as powerful as the impact with which the can hits the window and it ignites the riot that tears apart, loots, and burns down the pizzeria while Sal and his sons are helpless to do anything but watch. The frenzied mob, following the lead of ML (Paul Benjamin), who had previously expressed resentment at how enterprising Korean storekeepers are, turns its attention toward the Korean-owned grocery store, which is defended with a swinging broom by the owner, Sonny (Steve Park who, in a great bit of trivia, also played the non-sequitur and not-at-all-similar character Mike Yanagita in “Fargo” and is both times outstanding) until they decide there’s no need to damage his store, which is great for Sonny but it amplifies the alienation Sal and his sons feel.

In regards to Radio’s death, the guy was trying to choke Sal because Sal had the nerve to protect his shop and family until the police came in to stop him. Radio was belligerent the entire movie so I couldn’t empathize, although I’m not saying what the police did was right. That the crowd would blame Sal’s family for Radio’s death was irrational and just comes across as a reason for skewed vindication in the form of rioting and looting. This is what I mean about Lee’s objective look at blacks. The first time I saw the movie, my head hurt as I processed that the film’s director was black and offered the portrayals he did.

Also interesting to note in the scene is how Da Mayor, the alcoholic whose opinion carries no weight throughout the film, put himself in the way of danger in trying to be the voice of reason while Mother Sister, portrayed as wise as she monitors the neighborhood from her stoop, completely falls apart during the mob/death/riot scene. And, after her antagonism toward Da Mayor throughout the film, he’s the one that comforts her by being by her side the entire night.

In a highlight scene earlier in the film and one that depicts racism like I’ve never seen it depicted, various characters, one after another, address the camera (and the audience) as though they’re looking at a member of a race they hate and let loose with both barrels every appropriate slur they can think of (above). It’s a brilliant and thought-provoking scene and little is left to the imagination, which is the scene’s purpose. Here’s the scene with its lead-up: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cOxOR3x8FBQ In the “making of” documentary of the movie, which itself is entertaining (as well as a relief to know everyone really got along), it’s explained that Danny Aiello refused to use the n-word, which he does twice, because he found it offensive and would never use it himself. It took a lot of coaxing to finally get him to do it and it’s powerful when he does. I imagine it would have been difficult for the actors in the same way in the scene I describe in this paragraph.

In speaking or writing, I dislike using “n-word” in referencing it but I don’t have a desire and can’t bring myself to use the word itself. There’s no winning with it, especially when you reference it when you write. “N-word” is a cop-out but there’s no way around it. The actual word really is one of the worst words, if not THE worst word, in our language when it’s used in a derogatory way, yet it’s funny when blacks use it among themselves. That use of it hasn’t tempered the sting of the derogatory use of it at all, and it’s an odd word in that regard. I think if blacks could come up with an equally vicious derogatory name for whites, there would be less black-on-white violence. I’m sure countless articles have been written debating its use and at least one book as well.

In speaking or writing, I dislike using “n-word” in referencing it but I don’t have a desire and can’t bring myself to use the word itself. There’s no winning with it, especially when you reference it when you write. “N-word” is a cop-out but there’s no way around it. The actual word really is one of the worst words, if not THE worst word, in our language when it’s used in a derogatory way, yet it’s funny when blacks use it among themselves. That use of it hasn’t tempered the sting of the derogatory use of it at all, and it’s an odd word in that regard. I think if blacks could come up with an equally vicious derogatory name for whites, there would be less black-on-white violence. I’m sure countless articles have been written debating its use and at least one book as well.

I had a buddy at the steel mill I worked at (when I took a few years off school) who was half-black and half-white, six-four, two-eighty-five and simultaneously fearsome and hilarious. When you’re of mixed ethnicity – like me – you are reminded of it your entire life but not always in a bad way. In my case, it was rarely in a bad way and it’s made life interesting and definitely impacted my outlook and perspective. My buddy predated Chris Rock by decades when he told me, with his resonant voice and smooth delivery, “There’s black people, and there’s n____s. (Several second pause) I hate n____s” , which made us both laugh really hard.

I had a buddy at the steel mill I worked at (when I took a few years off school) who was half-black and half-white, six-four, two-eighty-five and simultaneously fearsome and hilarious. When you’re of mixed ethnicity – like me – you are reminded of it your entire life but not always in a bad way. In my case, it was rarely in a bad way and it’s made life interesting and definitely impacted my outlook and perspective. My buddy predated Chris Rock by decades when he told me, with his resonant voice and smooth delivery, “There’s black people, and there’s n____s. (Several second pause) I hate n____s” , which made us both laugh really hard.  He had a great and nonstop sense of humor and was a big-hearted guy but he’d rip your head and limbs off if he felt you deserved it. He was a good buddy to have. When we’d hang out and other blacks we knew that were his size or bigger would say something he even mildly took as offensive, they’d apologize and cower in his presence. Once while we were talking at work he said something to piss me off and it worked. I laughed sarcastically then, with everything I had, punched him in the stomach – which was eye-level to me – and ran as fast as I could, hiding from him the rest of the shift. He eventually caught and cornered me. All I can say is that I never punched him again and I’m still alive.

He had a great and nonstop sense of humor and was a big-hearted guy but he’d rip your head and limbs off if he felt you deserved it. He was a good buddy to have. When we’d hang out and other blacks we knew that were his size or bigger would say something he even mildly took as offensive, they’d apologize and cower in his presence. Once while we were talking at work he said something to piss me off and it worked. I laughed sarcastically then, with everything I had, punched him in the stomach – which was eye-level to me – and ran as fast as I could, hiding from him the rest of the shift. He eventually caught and cornered me. All I can say is that I never punched him again and I’m still alive.

South Park addresses the issue of that word in an exceptional episode entitled “With Apologies to Jesse Jackson”. For the point I’m making, you really only need to see the opening scene but the way the word is used the rest of the episode is extremely creative and it’s used a lot (42 times), which was a point of the episode. THAT’S writing. Plus, the buildup to and the fight Cartman has with a midget is hilarious. I don’t remember Cartman laughing this much in any other episode. It’s not even intentionally mean-spirited; he can’t help himself. If this episode doesn’t make you laugh and think, you have no pulse. Here it is: http://www.southparkstudios.com/full-episodes/s11e01-with-apologies-to-jesse-jackson

South Park addresses the issue of that word in an exceptional episode entitled “With Apologies to Jesse Jackson”. For the point I’m making, you really only need to see the opening scene but the way the word is used the rest of the episode is extremely creative and it’s used a lot (42 times), which was a point of the episode. THAT’S writing. Plus, the buildup to and the fight Cartman has with a midget is hilarious. I don’t remember Cartman laughing this much in any other episode. It’s not even intentionally mean-spirited; he can’t help himself. If this episode doesn’t make you laugh and think, you have no pulse. Here it is: http://www.southparkstudios.com/full-episodes/s11e01-with-apologies-to-jesse-jackson

Link added August 4, 2013 http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/argument-that-use-of-n-word-among-blacks-can-be-culturally-acceptable-is-rejected-in-ny-case/2013/09/03/54ddf806-14f8-11e3-b220-2c950c7f3263_story.html

Back to the DTRT:

Samuel L. Jackson does an exceptional job as the vibrant and verbally clever, poetic, and almost-Seussian neighborhood radio station DJ, Mister Señor Love Daddy (left), who serves as the film’s quasi-narrator and, along with Jade, its conscience as well. I also need to cite the comic relief provided by the late Robin Harris’ Sweet Dick Willie as he plays off ML and Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison), throughout the film and whose every sentence is exclamatory.

Samuel L. Jackson does an exceptional job as the vibrant and verbally clever, poetic, and almost-Seussian neighborhood radio station DJ, Mister Señor Love Daddy (left), who serves as the film’s quasi-narrator and, along with Jade, its conscience as well. I also need to cite the comic relief provided by the late Robin Harris’ Sweet Dick Willie as he plays off ML and Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison), throughout the film and whose every sentence is exclamatory.  Harris also contributes to the film’s edge by being potent in his confrontational or antagonistic scenes with Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito in yet another inspired portrayal in a movie full of them), Pino, and Sonny. One of the other guys I worked with at the steel mill was the spitting image of Harris, down to his clothes, hat, voice and delivery. He just lacked Harris’ sense of humor and wit. He wasn’t a popular guy.

Harris also contributes to the film’s edge by being potent in his confrontational or antagonistic scenes with Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito in yet another inspired portrayal in a movie full of them), Pino, and Sonny. One of the other guys I worked with at the steel mill was the spitting image of Harris, down to his clothes, hat, voice and delivery. He just lacked Harris’ sense of humor and wit. He wasn’t a popular guy.

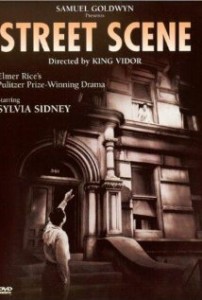

Lee borrows significant elements in DTRT from two earlier films. King Vidor’s” 1931 “Street Scene” takes place on a block in the course of a hot New York City day, there are antagonistic relationships, people get into each other’s personal business, someone monitors the block’s happenings from her stoop, and the day/film ends with a killing and neighborhood mob scene.

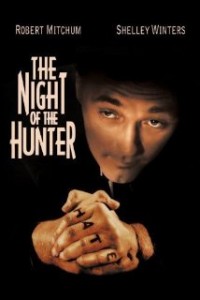

Lee borrows significant elements in DTRT from two earlier films. King Vidor’s” 1931 “Street Scene” takes place on a block in the course of a hot New York City day, there are antagonistic relationships, people get into each other’s personal business, someone monitors the block’s happenings from her stoop, and the day/film ends with a killing and neighborhood mob scene.  In Charles Laughton’s single credited directorial effort, 1955’s excellent “The Night of the Hunter”, Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum, phenomenal in the film) goes through the same love/hate conflict soliloquy that Radio Raheem does with Mookie using brass knuckles molded in the shape of those words.

In Charles Laughton’s single credited directorial effort, 1955’s excellent “The Night of the Hunter”, Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum, phenomenal in the film) goes through the same love/hate conflict soliloquy that Radio Raheem does with Mookie using brass knuckles molded in the shape of those words.

Here’s the version from “The Night of the Hunter” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X20XIg38GcE

Here’s the version from “Do the Right Thing” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pa-oUPTr9LI

If you’re gonna borrow, borrow from the best. The scene that sticks with me most from “Hunter” is the Shelley Winters underwater scene (right), which she apparently excelled at, having another big underwater scene later in 1972’s “The Poseidon Adventure.”

Back to Lee’s objective portrayal of blacks, specifically with his own characters: In “Jungle Fever”, it was Lee’s character Cyrus who, after Flipper confides in/brags to him about the affair, tells his wife Vera (Veronica Webb), who then tells her best friend, Drew (Lonette McKee), who happens to be Flipper’s wife. Besides the adultery itself, it’s especially painful for Drew because she’s half-white and herself grew up being a victim of racism within the black community.

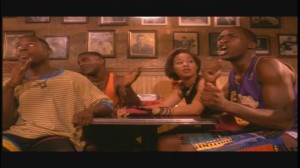

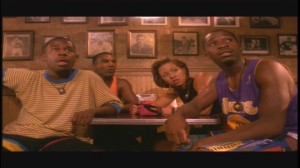

Back to Lee’s objective portrayal of blacks, specifically with his own characters: In “Jungle Fever”, it was Lee’s character Cyrus who, after Flipper confides in/brags to him about the affair, tells his wife Vera (Veronica Webb), who then tells her best friend, Drew (Lonette McKee), who happens to be Flipper’s wife. Besides the adultery itself, it’s especially painful for Drew because she’s half-white and herself grew up being a victim of racism within the black community.  Immediately after she throws Flipper onto the street in reaction to the affair (above), Drew’s friends get together to console her and the conversation “the war council” (as Cyrus refers to them) has about men and skin color is fascinating and insightful. I knew a girl in high school, very light-skinned and pretty, that other blacks used to sarcastically tease by calling her “Miss Black America.”

Immediately after she throws Flipper onto the street in reaction to the affair (above), Drew’s friends get together to console her and the conversation “the war council” (as Cyrus refers to them) has about men and skin color is fascinating and insightful. I knew a girl in high school, very light-skinned and pretty, that other blacks used to sarcastically tease by calling her “Miss Black America.”

I also had a buddy whose dark skin elicited similarly nasty comments from other blacks. Both were otherwise well-liked at the school. If you didn’t know that sort of intra-racial bigotry existed, and it also exists in other ethnicities, you know it now. Racism should really be called “differencism” because that’s what it’s really all about, being different. It’s also about intolerance, which will give you a headache if you spend too much time thinking about it.

I also had a buddy whose dark skin elicited similarly nasty comments from other blacks. Both were otherwise well-liked at the school. If you didn’t know that sort of intra-racial bigotry existed, and it also exists in other ethnicities, you know it now. Racism should really be called “differencism” because that’s what it’s really all about, being different. It’s also about intolerance, which will give you a headache if you spend too much time thinking about it.

If Cyrus would have kept the secret he was told in confidence to himself, everything would have been fine. The war council meeting ends with Drew, in dramatic resignation, saying, “…but none of that matters because my man is gone.” She’s the one that kicked him out without giving him a chance to explain himself; he didn’t want to leave. Justifiable or not, Drew let her emotions take over and dictate the decision to – at the time – end her marriage. It’s at this point I want to bring up a very smart move on the part of Jada Pinkett Smith, who recently acknowledged that she has an open relationship with this quote:

“I’ve always told Will: You can do whatever you want as long as you can look at yourself in the mirror and be okay.”

Talk about being a realist. To do what she’s doing, a woman has to be very confident in her husband’s love for her and a move like that doesn’t hurt in ensuring that love. Not only does she directly face the fact that men are men, she actually diffuses an aspect of extramarital affairs that make them appealing in the first place, the taboo element. That risk adds an edge that makes affairs alluring to men. Since Will has Jada’s OK, it’s not cheating and that edge is gone. I usually don’t care about the personal lives of celebrities (or anyone else) but this is so smart I had to mention it and it pertains directly to this film. I don’t know what transpired in their relationship prior to this arrangement but I’m sure there were bumps on the way to getting there. Women who find themselves in the position Drew does in “Jungle Fever” should keep it in mind and realize they’re not the first to have their husbands cheat on them.

Talk about being a realist. To do what she’s doing, a woman has to be very confident in her husband’s love for her and a move like that doesn’t hurt in ensuring that love. Not only does she directly face the fact that men are men, she actually diffuses an aspect of extramarital affairs that make them appealing in the first place, the taboo element. That risk adds an edge that makes affairs alluring to men. Since Will has Jada’s OK, it’s not cheating and that edge is gone. I usually don’t care about the personal lives of celebrities (or anyone else) but this is so smart I had to mention it and it pertains directly to this film. I don’t know what transpired in their relationship prior to this arrangement but I’m sure there were bumps on the way to getting there. Women who find themselves in the position Drew does in “Jungle Fever” should keep it in mind and realize they’re not the first to have their husbands cheat on them.  Any woman getting into a marriage thinking her husband will never cheat is naive, delusional, and lacking in perspective (all traits that would probably inspire a husband to cheat in the first place), especially nowadays (think Clinton, Spitzer, Weiner, Newsome, Patraeus, Sanford, Schwartzenegger, McGreevey). Just because you don’t know about it doesn’t mean it’s not happening. Women allowing their husbands to have extramarital affairs is nothing new and, as I’m implying, it can actually make a marriage and a couple’s mutual appreciation grow, which can only happen when a relationship is completely honest. The rush of the romance that results in the wedding rarely lasts, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Whether it will evolve into a more grounded and stable relationship or dissipate completely depends on the participants’ commitment to each other.

Any woman getting into a marriage thinking her husband will never cheat is naive, delusional, and lacking in perspective (all traits that would probably inspire a husband to cheat in the first place), especially nowadays (think Clinton, Spitzer, Weiner, Newsome, Patraeus, Sanford, Schwartzenegger, McGreevey). Just because you don’t know about it doesn’t mean it’s not happening. Women allowing their husbands to have extramarital affairs is nothing new and, as I’m implying, it can actually make a marriage and a couple’s mutual appreciation grow, which can only happen when a relationship is completely honest. The rush of the romance that results in the wedding rarely lasts, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Whether it will evolve into a more grounded and stable relationship or dissipate completely depends on the participants’ commitment to each other.  Here are government statistics on the marriage and divorce rates in this country: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/marriage_divorce_tables.htm The traits that people liked in each other before they get married often lose their charm as a couple gets used to each other and time and the tough situations are the real test of a marriage or any long-term commitment. As far as extramarital affairs go, sex and love are not synonymous and, once a woman gets past that idea and ditches her insecurities, the possibility of an arrangement like the Smiths have doesn’t seem so far-fetched. If you want to see a great comedy on the topic of extramarital affairs and their aftermath, watch George Cukor’s 1939 classic “The Women”, which has an outstanding cast. No men appear in the film, even though men are what the story is all about. I don’t think of Joan Crawford as being a good actress but she’s perfect in this movie.

Here are government statistics on the marriage and divorce rates in this country: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/marriage_divorce_tables.htm The traits that people liked in each other before they get married often lose their charm as a couple gets used to each other and time and the tough situations are the real test of a marriage or any long-term commitment. As far as extramarital affairs go, sex and love are not synonymous and, once a woman gets past that idea and ditches her insecurities, the possibility of an arrangement like the Smiths have doesn’t seem so far-fetched. If you want to see a great comedy on the topic of extramarital affairs and their aftermath, watch George Cukor’s 1939 classic “The Women”, which has an outstanding cast. No men appear in the film, even though men are what the story is all about. I don’t think of Joan Crawford as being a good actress but she’s perfect in this movie.

Here’s the entire article I got the Pinkett-Smith quote from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-2304171/Jada-Pinkett-Smith-open-marriage-rumours-Will-wants.html

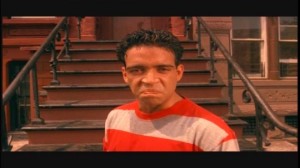

I’ve always referred to “Do the Right Thing” as “Don’t Do the White Thing” as Lee paints many of the black male characters in less than a positive light throughout the film, which is what I took most from it after my initial viewing. In his only scene, Clifton (John Savage) character is unflinching when he is harassed by a neighborhood group led by Buggin Out as he walks his bike up to his apartment building (left). The confrontation started because Savage’s character negligently (or belligerently) runs a bike tire over Buggin’s new white Air Jordans as he walks his bike on the sidewalk.

I’ve always referred to “Do the Right Thing” as “Don’t Do the White Thing” as Lee paints many of the black male characters in less than a positive light throughout the film, which is what I took most from it after my initial viewing. In his only scene, Clifton (John Savage) character is unflinching when he is harassed by a neighborhood group led by Buggin Out as he walks his bike up to his apartment building (left). The confrontation started because Savage’s character negligently (or belligerently) runs a bike tire over Buggin’s new white Air Jordans as he walks his bike on the sidewalk.

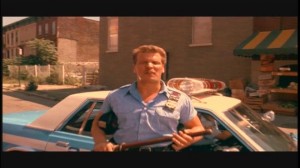

After Frank Vincent’s character warns the three-man group of late teens (that includes Martin Lawrence, who plays his character with a speech impediment) to not get his open-convertible Cadillac wet, they douse it in water from an open hydrant as he drives by (right). The police officers (Rick Aiello and Michael Sandoval) who respond to the scene and whose big scene is later in the film, arrive to take a report from Vincent’s character. By then, the culprits are long gone, which is the route the cops sarcastically recommend to Vincent. The same group that doused the Caddy are also hostile and belligerent in the scene leading up to the film’s climax. The film’s portrayal of black women is that of disapproval of and disappointment in the hateful attitude of their racist male counterparts.  Another less than flattering portrayal is that of Da Mayor (Davis, perfect and almost impish in the role), the philosophical neighborhood alcoholic who plays against real-life wife Ruby Dee’s Mother Sister for most of the story (left). Mother Sister spends her days monitoring the neighborhood from her stoop. The Puerto Ricans in the movie are portrayed in a peaceful and fun-loving way, the exceptions being the boom box standoff with Radio and the crowd scene after his killing.

Another less than flattering portrayal is that of Da Mayor (Davis, perfect and almost impish in the role), the philosophical neighborhood alcoholic who plays against real-life wife Ruby Dee’s Mother Sister for most of the story (left). Mother Sister spends her days monitoring the neighborhood from her stoop. The Puerto Ricans in the movie are portrayed in a peaceful and fun-loving way, the exceptions being the boom box standoff with Radio and the crowd scene after his killing.  In “Summer of Sam”, Lee plays fumbling and Uncle Tom-esque TV news reporter John Jefferson, whose loyalty to his own race is questioned on-camera by an interview subject whose strong Caribbean accent gives weight to her eh-vah-ree see-lah-bool (right).

In “Summer of Sam”, Lee plays fumbling and Uncle Tom-esque TV news reporter John Jefferson, whose loyalty to his own race is questioned on-camera by an interview subject whose strong Caribbean accent gives weight to her eh-vah-ree see-lah-bool (right).

Lee’s critical portrayal of blacks not only includes the intimidating and nonstop-jerk-to-anyone-who-isn’t-black Radio Raheem and the other examples I give; it’s full force with the character that ignited the incident that resulted in Radio’s death, Buggin Out (Esposito, ironically half-Italian and half-Puerto Rican himself but playing a black character).

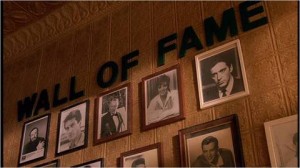

Lee’s critical portrayal of blacks not only includes the intimidating and nonstop-jerk-to-anyone-who-isn’t-black Radio Raheem and the other examples I give; it’s full force with the character that ignited the incident that resulted in Radio’s death, Buggin Out (Esposito, ironically half-Italian and half-Puerto Rican himself but playing a black character).  In a perfect example of an idle mind being the devil’s playground, Buggin, antagonistic toward Sal and his sons the entire movie (left), makes a racist cause out of insisting Sal include pictures of black celebrities on Sal’s Italian-American wall of fame (right), implying that if Sal doesn’t do it, it’s because he’s racist. In “Jungle Fever”, Lee includes similarly unlikeable characters played by Queen Latifah (below, a resentful, bigoted waitress), Sam Jackson (Flipper’s crack-addict brother, Gator) and Halle Berry (Viv, Gator’s co-addict and squeeze), who I didn’t even recognize when I first saw the film.

In a perfect example of an idle mind being the devil’s playground, Buggin, antagonistic toward Sal and his sons the entire movie (left), makes a racist cause out of insisting Sal include pictures of black celebrities on Sal’s Italian-American wall of fame (right), implying that if Sal doesn’t do it, it’s because he’s racist. In “Jungle Fever”, Lee includes similarly unlikeable characters played by Queen Latifah (below, a resentful, bigoted waitress), Sam Jackson (Flipper’s crack-addict brother, Gator) and Halle Berry (Viv, Gator’s co-addict and squeeze), who I didn’t even recognize when I first saw the film.  I knew Berry had a role but wasn’t really familiar with her and mistook Veronica Webb, who plays one of Drew’s friends and is pretty and light-skinned, for Berry. Especially because of her haircut, Webb looks more like Berry in the movie than Berry does. When I saw the movie a second time, I was floored that Berry was who she was, as she – like Pam Grier in “Jackie Brown” – goes toe-to-toe with Sam Jackson, an exceptionally versatile actor with a powerful screen presence, in one of Jackson’s defining roles. If you’ve never seen “Jungle Fever” or this clip, brace yourself: This is Halle Berry (graphic language warning): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jSidQZzJfcc

I knew Berry had a role but wasn’t really familiar with her and mistook Veronica Webb, who plays one of Drew’s friends and is pretty and light-skinned, for Berry. Especially because of her haircut, Webb looks more like Berry in the movie than Berry does. When I saw the movie a second time, I was floored that Berry was who she was, as she – like Pam Grier in “Jackie Brown” – goes toe-to-toe with Sam Jackson, an exceptionally versatile actor with a powerful screen presence, in one of Jackson’s defining roles. If you’ve never seen “Jungle Fever” or this clip, brace yourself: This is Halle Berry (graphic language warning): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jSidQZzJfcc

It gets better in these three clips in the Taj Mahal scene:

Taj Mahal 1 Taj Mahal 2 Taj Mahal 3

My favorite parts in what is essentially Gator’s scene are 1) anything Halle Berry says or does, 2) the way Flipper skips backwards and takes a boxer’s defensive stance after slapping the pipe out of Viv’s hands, and 3) after Flipper ends and leaves the confrontation, Gator’s eyes show regret then resignation before closing right as Steve Wonder’s “No no”s come in; the character’s most poignant moment in the film. Believe it or not, not only was Berry not recognized for her performance, Jackson was ignored by Academy voters in, again, one of his defining roles and possibly his best work. I can’t imagine him or anyone else doing a better job than he did in that role. He has to be inspiring for any actor to play against.

As great and significant a movie as “Do the Right Thing” is, I think the sum of its parts is greater than the whole, and the whole is amazing. That’s even more the case with “Jungle Fever” and “Summer of Sam”, which are progressively less focused, cohesive, stylized, and fluid than DTRT. While the scenes of “Sam” are interesting for all the effort put into them, the whole is a convoluted mess I’ve learned to like. All three movies just have so many great elements in them.

As great and significant a movie as “Do the Right Thing” is, I think the sum of its parts is greater than the whole, and the whole is amazing. That’s even more the case with “Jungle Fever” and “Summer of Sam”, which are progressively less focused, cohesive, stylized, and fluid than DTRT. While the scenes of “Sam” are interesting for all the effort put into them, the whole is a convoluted mess I’ve learned to like. All three movies just have so many great elements in them.  In Jungle Fever”, you get the real-life couple, Davis and Dee, charming neighborhood antagonists in DTRT, as a defrocked minister (a specific reason is never given, but Flipper implies his father has a black mark in his history) and his God-fearing wife. Davis (above) is very controlled but boiling beneath the surface – as emphasized by his close-ups – in his role while Dee (right), like Jackson and Berry, plays her character with the throttle wide open. She conveys how worn-down Lucille is as a result of her marriage and the stress and disappointment of having a crack addict and an adulterer for sons. Lucille doesn’t have a single relaxed, much less happy, moment and her switch is perpetually set on “worry” the entire film. Sciorra is effective as Gina and Mazar, Mastrogiacomo (a great one-episode prostitute on “Seinfeld”), Nick Turturro (Vinny taunts Paulie throughout the story, ultimately starting a fight with him), Imperioli, Rick Aiello and Michael Sandoval (back as their “Do the Right Thing” cops who change beats from Brooklyn to Manhattan to accommodate the movie), Teresa Randle (whose purring delivery steals any scene she’s in), and Michael Badalucco all add color (NPI) to the movie.

In Jungle Fever”, you get the real-life couple, Davis and Dee, charming neighborhood antagonists in DTRT, as a defrocked minister (a specific reason is never given, but Flipper implies his father has a black mark in his history) and his God-fearing wife. Davis (above) is very controlled but boiling beneath the surface – as emphasized by his close-ups – in his role while Dee (right), like Jackson and Berry, plays her character with the throttle wide open. She conveys how worn-down Lucille is as a result of her marriage and the stress and disappointment of having a crack addict and an adulterer for sons. Lucille doesn’t have a single relaxed, much less happy, moment and her switch is perpetually set on “worry” the entire film. Sciorra is effective as Gina and Mazar, Mastrogiacomo (a great one-episode prostitute on “Seinfeld”), Nick Turturro (Vinny taunts Paulie throughout the story, ultimately starting a fight with him), Imperioli, Rick Aiello and Michael Sandoval (back as their “Do the Right Thing” cops who change beats from Brooklyn to Manhattan to accommodate the movie), Teresa Randle (whose purring delivery steals any scene she’s in), and Michael Badalucco all add color (NPI) to the movie.  Brad Dourif and Tim Robbins portray Flippper’s architectural firm bosses in an adversarial way and don’t get much in the way of screen time or dimension. I only needed to see Dourif’s Oscar-nominated portrayal of Billy Bibbit in Milos Forman’s 1975 “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” – his first credited film performance (left, with Danny DeVito as Martini behind him) – to know that guy can act, although nothing he’s done since has matched that performance. It was a great role and he made it his own, like everyone else in that film did with theirs. What a movie. Michael Douglas won his first Oscar (Best Picture) as its producer.

Brad Dourif and Tim Robbins portray Flippper’s architectural firm bosses in an adversarial way and don’t get much in the way of screen time or dimension. I only needed to see Dourif’s Oscar-nominated portrayal of Billy Bibbit in Milos Forman’s 1975 “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” – his first credited film performance (left, with Danny DeVito as Martini behind him) – to know that guy can act, although nothing he’s done since has matched that performance. It was a great role and he made it his own, like everyone else in that film did with theirs. What a movie. Michael Douglas won his first Oscar (Best Picture) as its producer.

The time and place setting of “Summer of Sam” – volatile, grimy and glittery New York in the 70’s – is the film’s biggest draw for me and the actual Son of Sam storyline is its least interesting element, although it drives much of what happens in the film. Another big draw is it’s cast of good and recognizable actors. Where the other two films feature a mostly-black cast, the main characters in this movie are predominantly Italian and portrayed in stereotypical ways. The dat-dees-dem-dose neighborhood guys just hang out and work themselves into a frenzy easily, especially when they become rabid vigilantes in a drastically misguided attempt to hunt down the killer. Everyone argues instead of converses (which is entertaining only from a distance and loses its provincial charm when you move to New York and it becomes a daily way of life). Imperioli is the oily proprietor (is there any other kind?) of a filthy gay strip club and plays the character with a cowboy hat, Harry Reems mustache, and bad southern accent (I guess that’s what it is). I like seeing Ben Gazzara as the dapper neighborhood godfather but his performance is overdone, even for a New Yorker (not like it was in Vincent Gallo’s “Buffalo 66″, where he was excellent).

The time and place setting of “Summer of Sam” – volatile, grimy and glittery New York in the 70’s – is the film’s biggest draw for me and the actual Son of Sam storyline is its least interesting element, although it drives much of what happens in the film. Another big draw is it’s cast of good and recognizable actors. Where the other two films feature a mostly-black cast, the main characters in this movie are predominantly Italian and portrayed in stereotypical ways. The dat-dees-dem-dose neighborhood guys just hang out and work themselves into a frenzy easily, especially when they become rabid vigilantes in a drastically misguided attempt to hunt down the killer. Everyone argues instead of converses (which is entertaining only from a distance and loses its provincial charm when you move to New York and it becomes a daily way of life). Imperioli is the oily proprietor (is there any other kind?) of a filthy gay strip club and plays the character with a cowboy hat, Harry Reems mustache, and bad southern accent (I guess that’s what it is). I like seeing Ben Gazzara as the dapper neighborhood godfather but his performance is overdone, even for a New Yorker (not like it was in Vincent Gallo’s “Buffalo 66″, where he was excellent).  Mike Starr (Frenchy in “Goodfellas” and the schlock movie producer in “Ed Wood”), Bebe Neuwirth (great in everything), Patty Lupone (ditto), Jennifer Esposito, Adrien Brody (left, whose career has two gears, Oscar winner and “who cares?”, although he gives it everything he has in the film’s best role), Brian Tarantina (he was the explosive lunatic that golf-clubbed that guy into a coma and was himself killed by Burt Young’s character in the “Another Toothpick” episode of The Sopranos) and the neighborhood guys all give the screenplay better than it deserves. Anthony LaPaglia’s role as a detective is so minimal it’s almost a cameo. In a thankless role in another questionable casting move, Michael Badalucco portrays the killer, David Berkowitz.

Mike Starr (Frenchy in “Goodfellas” and the schlock movie producer in “Ed Wood”), Bebe Neuwirth (great in everything), Patty Lupone (ditto), Jennifer Esposito, Adrien Brody (left, whose career has two gears, Oscar winner and “who cares?”, although he gives it everything he has in the film’s best role), Brian Tarantina (he was the explosive lunatic that golf-clubbed that guy into a coma and was himself killed by Burt Young’s character in the “Another Toothpick” episode of The Sopranos) and the neighborhood guys all give the screenplay better than it deserves. Anthony LaPaglia’s role as a detective is so minimal it’s almost a cameo. In a thankless role in another questionable casting move, Michael Badalucco portrays the killer, David Berkowitz.

I realize this is just me but all you have to do is allude to nudity and sex scenes and I get the point and the movie can move forward. I don’t need to see either and there’s a lot to be said for leaving both to the imagination. Women appear topless and there’s a lot of almost-nudity in all three films and all three have graphic sex scenes I find gratuitous. If you took the sex-related scenes out of “Sam”, the movie would be cut in half. If the title was “Summer of Sex”, it would be justified. I enjoyed “Inside Man”, so I know Lee can direct a good movie without nudity or graphic sex.

Ernest Dickerson worked the camera in “Do the Right Thing” and “Jungle Fever” (and did outstanding work on “Malcolm X”) and I think his work is underappreciated. He does wonderful things with light in both movies and his spare use of angled shots to emphasize uncomfortable scenes is very effective. I also like the way having actors on dollies – which he also uses sparingly – makes you really focus on their interaction and dialogue. Maybe it’s because of Dickerson’s showiness, which I like, that he’s never been nominated for an Oscar. I tell myself Oscar voters just saw five better-looking movies the years he shot the movies I mention. The Taj Mahal scene in “Jungle Fever” is almost enough of a reason by itself to see the film (above). The Taj Majal is a tall, abandoned (even by rats) building in a not-nice neighborhood and full of not-nice people smoking crack but the fluid, hazy way the scene is lit, shot, and cut is beautiful. That already great scene is augmented by Stevie Wonder’s 1973 “Living for the City”, which plays in its entirety. The scene and song emphasize each other’s power and Wonder’s voice never sounds greater than it does at the end of the scene/song. You’re forced to focus and dwell on it as well as associate it with what you’re seeing (the volume might have be notched up at the very end). Spike Lee essentially gave the song an appropriate and amazing music video he has to be proud of.

I think Lee is smart and interesting and his films are energetic and insightful. There are still a few I haven’t seen. In the three I highlight here, he lends a critical eye to critical eyes and does a great job of making his points. “She’s Gotta Have It” and “School Daze” are wonderful in their sincerity and simplicity and “Crooklyn” is an intimate and charming autobiography. “Sucker Free City” was different in that it took Lee out of New York and put him in San Francisco.  I lived in different cities in the Bay Area – including Oakland near the Fruitvale BART station that is the setting for the current movie about a controversial killing – and explored most of the others, including the specific area SFC is set. Knowing the Bay Area and its people, I found the storyline a little hard to digest; people in the Bay Area just aren’t as dramatic, overdone, and unnecessarily complicated as they are in New York. “Malcolm X” was a great, epic production and was clearly made to offer an objective, sympathetic perspective on its culturally significant subject (but I think it’s safe to say “Do the Right Thing” is Lee’s opus). I knew nothing about Malcom X or Islam before the movie so it was enlightening as well as entertaining. I felt my own skull burning during those hair-straightening treatments and I liked the zoot suit dance scene, which may have been indulgent on Lee’s part but it’s energetic and fun. That KKK night scene with the giant moon in the background was almost overwhelming in how good it looked (you can’t miss it above). The whole movie was done well.

I lived in different cities in the Bay Area – including Oakland near the Fruitvale BART station that is the setting for the current movie about a controversial killing – and explored most of the others, including the specific area SFC is set. Knowing the Bay Area and its people, I found the storyline a little hard to digest; people in the Bay Area just aren’t as dramatic, overdone, and unnecessarily complicated as they are in New York. “Malcolm X” was a great, epic production and was clearly made to offer an objective, sympathetic perspective on its culturally significant subject (but I think it’s safe to say “Do the Right Thing” is Lee’s opus). I knew nothing about Malcom X or Islam before the movie so it was enlightening as well as entertaining. I felt my own skull burning during those hair-straightening treatments and I liked the zoot suit dance scene, which may have been indulgent on Lee’s part but it’s energetic and fun. That KKK night scene with the giant moon in the background was almost overwhelming in how good it looked (you can’t miss it above). The whole movie was done well.

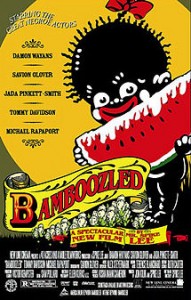

“Bamboozled” is often nails-on-a-chalkboard for me and a blatant “Network” rip-off (I said the something similar about “The Hospital” so what do I know?) but I’ll still watch it from time to time for Lee’s energy. Damon Wayans’ TV executive character gives a new definition to “Uncle Tom”. I’ve never heard anyone talk in such an affected way and he makes Cary Grant sound like Ralph Kramden or Fred Flintstone (same difference). It just occurred to me he may be doing a Louis Farrakahn impression but I refuse to get rid of the Fred Flintstone reference. The best thing about the movie is its Black Sambo/watermelon poster, which is biting in its irony and beautiful in its striking use of color. It also lists Michael Rappaport as one of the movie’s “Great Negroe Actors”. Somebody has a sense of humor. The poster for “Bamboozled” is one of five I have hanging in my home and it’s the only one of a movie not distributed by the company I worked for. That’s like.

“Bamboozled” is often nails-on-a-chalkboard for me and a blatant “Network” rip-off (I said the something similar about “The Hospital” so what do I know?) but I’ll still watch it from time to time for Lee’s energy. Damon Wayans’ TV executive character gives a new definition to “Uncle Tom”. I’ve never heard anyone talk in such an affected way and he makes Cary Grant sound like Ralph Kramden or Fred Flintstone (same difference). It just occurred to me he may be doing a Louis Farrakahn impression but I refuse to get rid of the Fred Flintstone reference. The best thing about the movie is its Black Sambo/watermelon poster, which is biting in its irony and beautiful in its striking use of color. It also lists Michael Rappaport as one of the movie’s “Great Negroe Actors”. Somebody has a sense of humor. The poster for “Bamboozled” is one of five I have hanging in my home and it’s the only one of a movie not distributed by the company I worked for. That’s like.

One Lee-directed movie whose DVD release I’m anticipating is “Bad 25”, a 25th anniversary salute to Michael Jackson’s album, which blew “Thriller” (whose success baffles me) out of the water and is an exceptional pop album, possibly the best work of both Jackson and producer Quincy Jones. It was also the last album collaboration between the two and Jackson’s albums went downhill from there, although I like the song “Stranger in Moscow” and its accompanying video. I also like the appearance of Chris Tucker, Marlon Brando, Michael Madsen (Virginia’s brother), and Billy Drago (the guy who played Frank Nitti as a reptile in 1987’s ”The Untouchables”, Brian De Palma’s best film) in the video for “You Rock My World”. Lee directed Jackson’s Rio-set and Rio-involved music video for “They Don’t Really Care About Us.”

One Lee-directed movie whose DVD release I’m anticipating is “Bad 25”, a 25th anniversary salute to Michael Jackson’s album, which blew “Thriller” (whose success baffles me) out of the water and is an exceptional pop album, possibly the best work of both Jackson and producer Quincy Jones. It was also the last album collaboration between the two and Jackson’s albums went downhill from there, although I like the song “Stranger in Moscow” and its accompanying video. I also like the appearance of Chris Tucker, Marlon Brando, Michael Madsen (Virginia’s brother), and Billy Drago (the guy who played Frank Nitti as a reptile in 1987’s ”The Untouchables”, Brian De Palma’s best film) in the video for “You Rock My World”. Lee directed Jackson’s Rio-set and Rio-involved music video for “They Don’t Really Care About Us.”

On the topic of music, I own and enjoy the “Do the Right Thing” and disco-infused “Summer of Sam” soundtracks. Both albums feature various artists and the song collections mark the time of each movie’s setting. The soundtrack for “Jungle Fever”, which I also own, is all Stevie Wonder original songs for the movie and doesn’t include “Living for the City.” I have all of Wonder’s significant albums and, while the soundtrack is enjoyable, his best/70’s music set the bar too stratospherically high for the work that followed. The guy won Grammys for Album of the Year in 1974, 1975 and 1977. When Paul Simon accepted the Grammy® for Album of the Year in 1976 for Still Crazy After All These Years, he ended his acceptance speech by saying “Most of all, I’d like to thank Stevie Wonder, who didn’t make an album this year” (Simon also won in 1987 for Graceland). Here’s the speech: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkA_qT0KSqI I can’t find a list of all the Album of the Year recipients on the website for The Recording Academy ®. This Wikipedia listing seems to show the year the award was given as opposed to the year of release. I’ve never seen a list of winners before: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grammy_Award_for_Album_of_the_Year

Believe it or not, this is still a review of movies:

All three Lee movies that are the focus of this writing feature thoughtful, energetic, and entertaining opening credits. “Jungle Fever” and “Summer of Sam” have great closing credits and the latter additionally bookends itself appropriately with Jimmy Breslin – with whom the Son of Sam killer corresponded during his rampage – first introducing the audience to the movie (left) then sending us off at the end (below) to Sinatra ‘s “New York, New York” playing over the urgent newspaper headline closing credits. I like when Breslin refers to the killer as “that sick fuck” at the end of the movie, which is significant and appropriate considering his role in the actual events. Imagine having those letters directed at you.

All three Lee movies that are the focus of this writing feature thoughtful, energetic, and entertaining opening credits. “Jungle Fever” and “Summer of Sam” have great closing credits and the latter additionally bookends itself appropriately with Jimmy Breslin – with whom the Son of Sam killer corresponded during his rampage – first introducing the audience to the movie (left) then sending us off at the end (below) to Sinatra ‘s “New York, New York” playing over the urgent newspaper headline closing credits. I like when Breslin refers to the killer as “that sick fuck” at the end of the movie, which is significant and appropriate considering his role in the actual events. Imagine having those letters directed at you.

As I started this writing by talking about my childhood daydream of living in New York City and how the New York backdrops and edge of the films are significant in their appeal for me, it’s appropriate that I would bring it home by referencing “Sam”‘s Breslin/Sinatra ending. My comments critical of New Yorkers are not confined to my writing; I made them repeatedly to people I lived near and worked with in Manhattan. In conversations where I’d be especially cynical, co-workers would laugh and say, “Yep, Dan’s a New Yorker now”, to which I’d object, even though I understood it was a compliment and I’d have to fight from laughing along with them.